William Clapp House

195 Boston Street

Dorchester, MA 02125

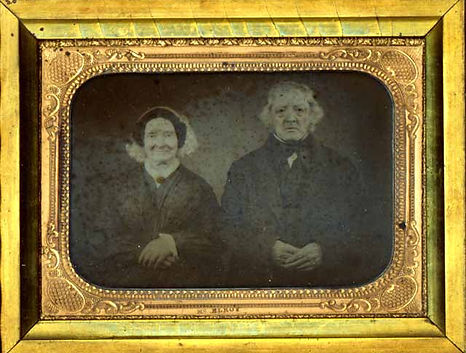

William Clapp, son of Capt. Lemuel and Rebecca (Dexter) Clap, was born in Dorchester on March 3, 1779, and died on Feb. 29, 1860. He followed the business of his father and carried on, till near the close of his life, the large and well-known tan-yard on the corner of what is now Boston Street and Willow Court, for many years the largest tannery in Dorchester. He built a house at the time

of his marriage to Elizabeth Humphreys on the opposite corner of the Court (north from the tan-yard and a few rods east of his father's), which is now the headquarters of the Dorchester Historical Society. The William Clapp House was built in 1806. Only two years earlier, Dorchester Avenue, located one block to the east, had been cut through this area as a turnpike or toll road linking Dorchester Lower Mills with Boston.

The House serves as the headquarters of the Dorchester Historical Society and as the site of its meetings. Many of the rooms are furnished with objects from the 19th century and from Dorchester's history. The House includes an original cellar kitchen with cooking implements of earlier years. The William Clapp House provides space for the Society's library and for a large collection of Dorchester Pottery, Gleason Pewter, Baker Chocolate, etc. The barn houses a large number of agricultural and carpentry tools and implements.

Architecture

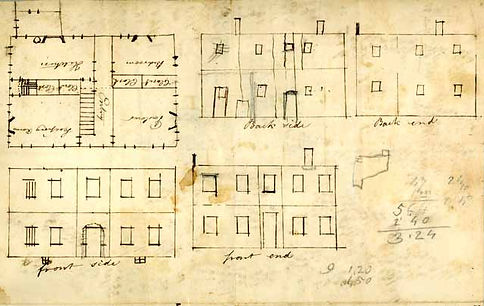

The William Clapp House is a typical two-story four-over-four Federal-style mansion house with a hip roof. It has a square plan facing SE to Boston Street, five bays wide by five bays deep with a later rear two-story, gable roof, wood frame, wing and lean-to. The main building contains four brick corner chimneys and central gable dormers on the SE and NW elevations. The SW and NW elevations of the main building are common bond brick. The SE and NE elevations and all elevations of the rear wing are clapboard. The windows of the main block are sash type with six over six arrangement. Those of the SE and NE elevations have moulded trim and slipsills. The main entrance consists of an open porch and vestibule with double doors containing large translucent upper panels. The SW elevation has a central recessed single door and fanlight facing a large concrete terrace. The building stands on a stone block foundation. Additionally, a large two-story, gable roof, wood frame, rectangular barn and a late 19th-century/early 20th-century carriage house are located on this property. Exterior renovations and repainting of the William Clapp House were completed in in the years 2015 and 2016.

The 19th Century

In 1806 William Clapp was twenty-seven years old. The son of Capt. Lemuel Clap, William had built up the family business into the largest tannery in Dorchester. The prosperous young man was about to embark on a new phase of his life. William had just become engaged to Elizabeth Humphreys, the daughter of James Humphreys, a respected Deacon of the first Parish Church. The marriage joined two of Dorchester's oldest families.

Upon the betrothal, William began to build a new home on land deeded to him by his father Lemuel. He engaged Samuel Everett, a talented housewright, to design the building. Everett incorporated the prevailing neoclassical or Adamesque style inspired by English buildings. Boston was in the forefront of the new style, and both William and his builder would have been well-acquainted with its principles. In fact, the style had been almost single-handedly promoted in American by Boston architect Charles Bulfinch, who had designed the Massachusetts State House and all of Boston's Federal-era public buildings. Builders across the nation emulated the style, making Bulfinch the major influence on architectural taste in the young republic.

The Clapp House was built using bricks from the brickyard in South Boston that was operated by William's brother Richard. The east and north sides of the house were sheathed in clapboard, and painted, as was the fashion. Although often called a farmhouse, the Clapp House is essentially a large free-standing city home, emulating the fine brick homes that were being built along Washington Street in the South End and on Beacon Hill at this time. The symmetrical arrangement of windows, the hipped roof, and the siting on a small rise are all typical of high-style Federal homes. While William's house is more modest in scale, he did incorporate as many of the stylish Neoclassical elements as he could afford. These include the double parlor arrangement, dentil molding and comb-molding details in the south parlor, and the fanlight and sidelights of the front door. The original columned portico was replaced by the present Italianate entryway in the 1870s.

Social Changes in the 19th Century

William Clapp was born in 1779 and Elizabeth in 1783. The Federal-era generation of which they were a part had been raised to aspire to economic prosperity and social mobility.

With his business secure, William Clapp began to take a more active role in town affairs. He served as town selectman, on the school board, on the highway committee, and other town posts. He also served one term as a representative to the Great and General Court of Massachusetts (the state house of representatives). William Clapp was an active member of the Dorchester militia for most of his life. Like his father, he rose to the rank of Captain. The colonial militia had played a vital role in protecting the town. Lemuel Clap's Company served at Dorchester Heights during the British evacuation of Boston in the Revolution. However, by the 1820s, participation in a local militia was largely a social outlet. Membership in such companies helped establish social and business contacts. William's duties seemed to be mostly arranging for music for the musters, organizing the drills, and arranging for the copious refreshments which followed.

While skilled tradesmen such as William Clapp were proud to be part of the prosperous class of "mechanics," they hoped for more for their sons. With hard work and the right connections, young men could expect to rise quickly in society in the Federal era. Upwardly-mobile families like the Clapps educated their sons to be part of a growing professional class and prepared their daughters to be the wives of such young men.

The Clapp House was spacious, but it quickly filled to overflowing. Elizabeth bore nine children between 1808 and 1821. Two died in infancy, but seven lived at least into their teens. It was common to lose children to childhood diseases or accidents, and Elizabeth must have felt extremely lucky to have the majority of her children remain healthy. Sadly in 1838, the three youngest - Rebecca, aged 21; James, aged 19; and Alexander, aged 17 - died within four days of each other when typhoid swept through Dorchester. It was a devastating blow to the family.

About this time, young Lemuel, who was engaged to be married, supervised the addition of a new kitchen and servant wing onto the rear of the house, partly in response to the family's plans to expand their agricultural business. Lemuel and his bride Charlotte Tuttle moved into the mansion house in 1840. As his siblings married and moved out, Lemuel remained to raise his family and care for his aging parents. Frederick and his new wife Martha Blake built next door.

In the 1830s, Dorchester was still a small town of about 2,000 families. William's adult children socialized within a small circle of extended family and old Dorchester families. The children sometimes attended lectures and musical program and were occasionally taken into Boston for special events. Much of their social and political life revolved around the church. While the Clapps were nominally Congregationalists, as members of the First Parish they practiced the popular "new religion" (Unitarianism). Perhaps influenced by their liberal pastors, the Clapps supported a number of progressive causes. They were especially ardent abolitionists, aligning themselves with the "Garrisonians," the most extreme branch of the anti-slavery activists in New England.

At mid-century, Dorchester was a mix of old farms and burgeoning suburban neighborhoods. William's grandchildren took on the trappings of middle-class Victorian householders. Most married into local families. They went to tea or drank lemonade on open porches as their children played on grassy lawns in the shadow of the old manse.

Agricultural Pursuits

William Clapp and his sons were involved in the hybridization of apples and pears, and the lands north of the Clapp House were cultivated as a fruit orchard as early as 1810. Around 1839 William and his sons embarked on a program to turn the farmstead into a modern agricultural business. While the main focus was on their orchards, part of the plan included expanding dairy production.

Before the Civil War, the most important dairy product was butter, not milk. New England cream was unmatched for its superior butterfat content, and the region's butter and cheeses were highly prized. In 1806, when newlyweds William and Elizabeth set up housekeeping, they probably kept three or four milk cows to meet the needs of their household. The dairy herd was later expanded as a result of the planning process at the end of the 1830s. The construction of the addition at the rear of the house may have been a result of this planning process as well.

Butter and cheese were processed in the basement of the "new wing." After the milking was done, hired dairymaids separated the butter from the raw cream using an efficient paddle churn. The butter was salted, put up in wooden tubs, and stored in an insulated tin-lined cooler until it was sent to market. Cheese was aged in the same cellar room.

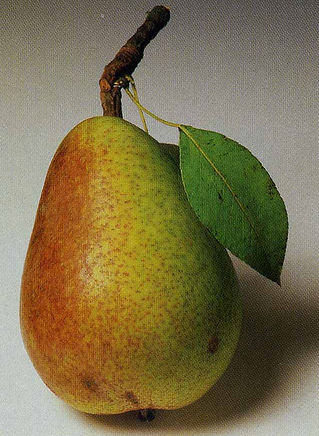

The dairy remained a small local operation, but not so the orchard business. The Clapps were among a number of farmers in Dorchester and Roxbury experimenting with improved varieties of vegetables and fruits. From Frederick's diary of 1847-51, we know that the family cultivated potatoes, beets, beans, rutabagas, and corn. These were well-established staple crops and not particularly innovative. The real interest of the brothers was in cultivating new varieties of fruit trees, especially pears. They also grew plums, strawberries, currants, and many other types of berries. They became very successful, even shipping plants to Europe. During the early 19th century, the Massachusetts Horticultural Society was supported by the local gentry of Dorchester and other Boston-area towns. William Clapp and his sons, Lemuel, Frederick and Thaddeus, all joined the new society and submitted their fruits for the annual award ceremony. The creation of the "Clapp's Favorite Pear" in 1840 was a local marvel that proved profitable for the Clapps. The Clapp's Favorite Pear was the hybridization of the Flemish Beauty Pear and the Bartlett Pear. The fact that it was an early ripening pear made the fruit available in mid to late August, at a time when fruits were thought to have medicinal qualities and relatively short periods of shelf life. Several of the streets in the St Margaret's / Boston Street area were named for pears grown on the Clapp estate, including Mount Vernon, Harvest, and Dorset Streets.

Each of William Clapp's sons contributed to the success of the fruit business. Thaddeus, who had studied at Harvard College, was the scientist. He experimented with many hybrids, published his findings in scientific farming journals, and earned a reputation in horticultural circles. According to family tradition, Lemuel had the honor of planting the first Clapp's Favorite Pear seed. He seems to have been the manager of the business, setting wages, hiring workers, and keeping accounts. Frederick was the real farmer of the team. He could be found haying, planting crops, improving root cellars, and tending animals. He even cultivated a peach orchard. However, New England farms declined after the Civil War, and the business declined. By 1884, Frederick's son Edward Blake Clapp, a florist, had transformed the farm into a local nursery complex focusing on green-house cultivated flowers, while his cousin William Channing Clapp maintained a small dairy.

Neighborhood Development

Mt. Vernon Street was developed c. 1870 over part of the Clapp orchard and was a harbinger of more intensive street construction. The setting out of Mt. Vernon Street coincided with the annexation of Dorchester to Boston, an event that triggered Dorchester-wide housing development, only to be curtailed by the Financial Panic of 1873. Mt. Vernon Street has an important collection of early 1870s Italianate / Mansard residences. Harvest Street, like St. Margaret Street and Mayhew Street to the south, was cut through the former Clapp orchards during the 1890s and is lined with a diverse collection of Queen Anne, Colonial Revival, and three-decker housing.

Mayhew Street is an important repository for simple, minimally ornamented Late Federal / Greek Revival dwellings. Set out as a cul-de-sac named Clapp Place as early as 1830, Mayhew Street's north side is built up with wooden 1830s and ‘40s dwellings, which are characterized by distinctive, horizontally massed structural components consisting of a main block and one or two lateral wings.

This street provides a fascinating opportunity to study a suburban subdivision that pre-dates the introduction of the railroad to Dorchester by more than a decade. Clapp Place seems to have been developed as a compound for the family and friends of the William Clapps. Its early residents were engaged primarily in agricultural pursuits. The first house on the street was probably the William Channing Clapp House at 8 Mayhew Street. Mayhew Street, a.k.a. Clapp Place, evidently started out as a driveway leading to the William Channing Clapp farm house, which remained under Clapp ownership until at least the early 1900s. By 1850, nine houses bordered this dirt-covered country lane. 31 Mayhew Street is an Italianate house owned by A.H. Clapp during the late 19th century; 32 Mayhew Street, a sparely ornamented Greek Revival house was owned by Alfred H. Clapp and his heirs until the early 20th century; 38 Mayhew Street was occupied by Frederick Weiss who married Mary Clapp, daughter of Richard and granddaughter of Lemuel, from the 1860s until at least the turn-of-the century; and 42 Mayhew was owned from at least the 1850s until the early 1900s by William Blake Trask. His family operated the Trask Pottery Co. at Commercial Point and he married Mary's sister Rebecca. A carpenter by trade, he may have been involved as a builder in the development of Mt. Vernon Street c.1870. He was for many years active in the New England Historical Genealogical Society and the Dorchester Historical Society. During the early 1900s, he lived in the Capt. Lemuel Clap House, the early 18th century house that is part of the Dorchester Historical Society property.

221/223 Boston Street is another survivor from the mid-nineteenth century. By 1894, Martha Clapp, widow of Frederick and daughter-in-law of William Clapp, the tanner who built 195 Boston Street in 1806, lived in this double Greek Revival house.

The Dorchester Historical Society acquired the Clap/Clapp houses in the 1940s from Frank Lemuel Clapp, whose wife had died earlier. Frank was a loyal supporter of the Dorchester Historical Society and remained as caretaker until his death in the 1950s.